He was humble, which is a rare quality in styling. He was a better person because of it.

Some argue that true artists are those who give their inner conflicts outward. A glance at Dick Teague’s resume would not be enough to believe otherwise. He must have experienced serious inner turmoil – how else could you explain AMC Pacer’s success?

This is not to trivialize the work of one the most resourceful automotive designers over the past 50 years; one who could create a new model with only a vivid imagination, and access to a parts box. He was often on the margins and without access to finance but he knew how make a little go far. Teague, a man who lived a full life filled with incidents, overcame many obstacles to design some of the most instantly recognizable cars to ever emerge from North America. His name is still a mystery, somewhere in the midst of fuzzy appreciation or absolute obscurity.

While Bill Mitchell and Harley Earl continue to be revered, and Gordon Buehrig & Howard ‘Dutch’Darrin are cult status respectively, it’s time that torches were set for the man who accomplished an almost impossible feat: He made AMC hip. Richard A. Teague was born in Los Angeles on Boxing Day 1923. He was blessed to live to adulthood. Although a troubled and frequently perilously ill childhood, Richard A. Teague made an impact early on when his artist mother Thia offered him a role as a short film director in the popular Our Gang series. This was a job that turned him into a her. Dick, however, became Dixie.

But his showbiz career was short-lived. After a day of filming, Teague rode in the back seat of his car, but he couldn’t get home because a drunk driver lost control, spun out and hit the car in which he was riding. The five-year old was propelled through his windscreen in the collision. He survived, but tragically, he lost one eye. He died just a few months after his father was killed in a similar accident.

uo

uo

These calamities did not hinder Teague’s ability to drive. In fact, Teague had discovered hot rodding as a hobby in his teens. The young tearaway, a friend and contemporary to tuning deities Ed Iskenderian (and Stu Hilborn), took up street racing on a ’32 Ford hiboy roadster. He was then able to take to the Muroc dry lakes with Johnny Law.

Teague, a disabled man, was unable to join the World War Two draft. He dropped out of art school and began his first job as a professional designer at Northrop Aircraft Corporation. He was an illustrator for the XP-61 Black Widow Night-fighter Project. After that, he responded to an advertisement in the Los Angeles Examiner stating: “Interviewing for a potential automobile designer to visit Detroit and join a growing group of General Motors designers.”

The then-23-year old answered the interview in October 1947. He was promoted to the Korean war-depleted style department the next March. His time in Oldsmobile was short-lived, as the starry-eyed futurist failed to connect with Art Ross, the studio head. Teague was “…exported from the company after being loaned to Cadillac.

His new wife and he moved to New Mexico. He also took a job as a defense contractor, but it was not rewarding. The pull of writing cars kept him resolute. A phone call from Frank Hershey, a former GM man, would change his life. “How would it be to be chief stylist at Packard?”

The once-proud marque was afflicted by its archaic inline engines and new V8s. The 1580 East Grand Boulevard Detroit designers (which included John Z. DeLorean ) knew that they were up against it. The company emerged victorious, however, thanks to Jack Nance’s leadership. His Caribbean production car was able to temporarily halt the inevitable, despite the Teague-styled Packard Balboa (predictor show queens) and the Teague-styled Packard Balboa (predictor show queens). He decided to leave the company in 1958 after it collapsed.

It was Chrysler that Teague was sent, and soon became involved in a bitter turf war between William Schmidt, director of design, and Virgil Exner vice-president. Teague was eventually forced to leave the company by Schmidt and his rivals to join an external consultancy that was supposed to be Chrysler. None of his efforts ever became three-dimensional reality. Teague later wrote in Road & Track magazine that “it was the worst 18-months of my life.”

However, things improved. Teague was appointed assistant director of styling at American Motors on September 3, 1959. The Wisconsin brand suffered from a dull image. Teague’s youngest son, who was horrified at the thought of seeing his father in his Rambler company car, demanded that he be dropped off just a few blocks from school. Teague would change that perception by being named styling director in three years and vice-president of AMC after five years (a position he would keep for 23 years, an industry record). The Tarpon was his first major project. It was a small coupe of medium size that could have been matched for style and pace by Ford’s new Mustang. Roy Abernethy, president of AMC, didn’t think there was enough demand for such a vehicle. He canceled it. He requested that the styling elements of the Marlin be transferred to a larger vehicle. Marlin, the result was a failure in sales. The original 1966 AMX show-stopper, which went from rendering to finished item in 60 days, was then followed.

That was just the beginning. Robert Evans, the newly appointed chairman, was able to convince Teague and the suits that AMC required a “pony vehicle”. Or two. AMC was able to launch the Javelin AND AMX within six months in 1967-’68, the former model being a Javelin reduced by 12 inches. In its first year, 55,000 Javelins were moved. The Pennsylvania-based Penske squad won Trans-Am competition in 1971-’72, and there was positive publicity in the motoring press. Conservative board members were quickly sated.

This gave Evans and Teague a platform to pursue more innovative projects, as they sought to appeal to a younger audience. AMC was buoyed by the positive response to the non-running AMX II Supercar at the Chicago Auto Show ’69, and sought to counter the Ford-sponsored De Tomaso Pantera by offering its own mid-engined competitor, the AMX III. Giotto Bizzarrini, a Mercurial Italian engineer, was hired to design the car’s semi-monocoque frame. AMC’s familiar 390ci bent-eight engine would be located amidships. Teague created a dramatic outline that rivaled the best Latin exotica for visual drama. It was unveiled in Rome in March 1970 to a select group of people. Although the AMX III was stunning, dramatic, and powerful, it never had a chance. The project was canceled because of the high build costs. Teague, who is not known for wasting opportunities, was still devastated. However, he was able to keep one of six prototypes.

Even though a supercar might have been prohibitive in cost, Teague didn’t lack the operating budget to support more mainstream products. Teague seemed to have an inborn ability to make the most of every dollar, using interchangeable inner doors, glass, and other parts. Pragmatism was crucial: see the much-maligned Gremlin by AMC, which attempted to break into the subcompact market. There was no way to build a new car with the money that Tinder had. Teague instead took the Hornet platform and reduced the wheelbase. He is said to have drawn the car’s outline using a sick bag on his return flight from Detroit. Its long nose and cropped tail made it stand out enough for Driver and to comment on: “It borrows nothing from anyone.”

The Gremlin was a shambles, but it didn’t hurt that it was launched April 1, 1970 670,000 of which were transferred over eight years. This made for a nice profit on a $5 million development expense. It was a marvel of subsistence engineering, design genius.

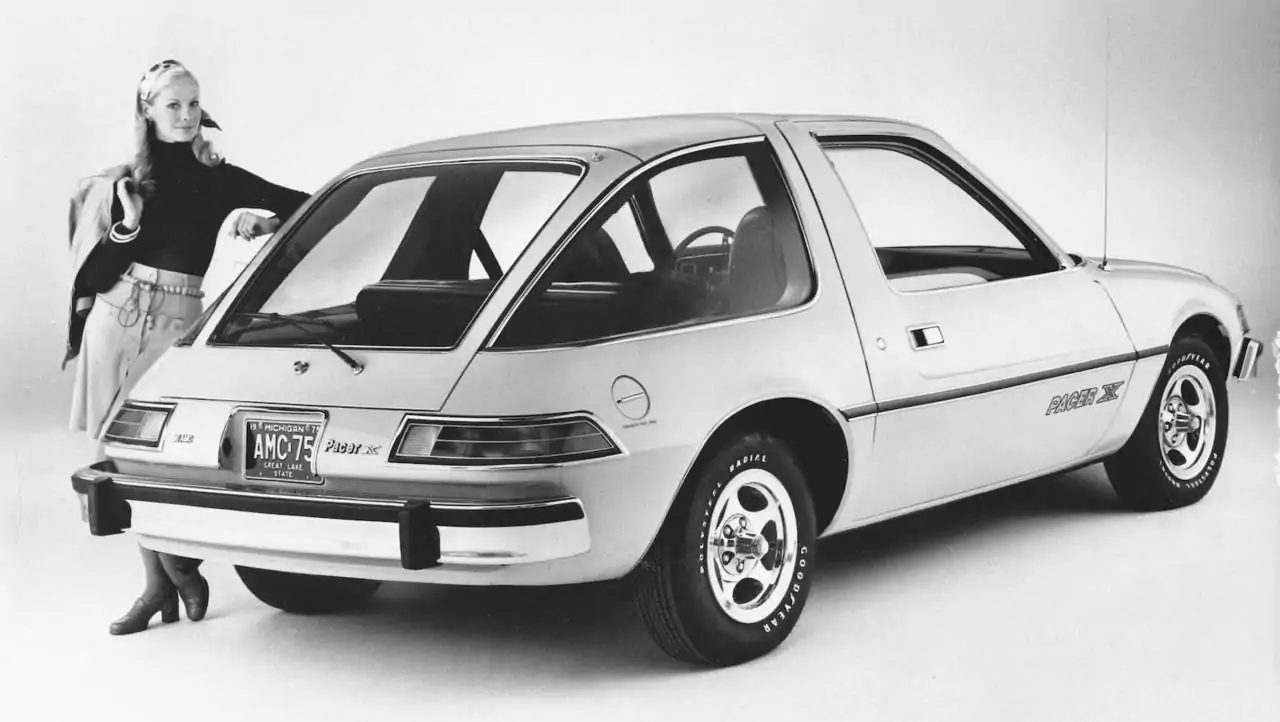

Teague’s reputation for being a lateral thinker was cemented by the car that followed. He was asked to design what was effectively a subsub-compact. His various ideas were rejected during heated shareholder meetings in 1971. The original design was to make a light economy car. However, the reality of production was quite different. Teague desired lightweight materials, front-wheel drive, and Wankel’s rotary power. He was forced to use the 88-hp inline six (and later V8) instead. This resulted in what Teague described as a “football with wheels”. Outwardly, the Pacer was about as radical as cars got during that period.

Radical, however, is not something everyone likes. Despite many positives (like a drag coefficient of 0.32 Cd), the Pacer was still a major disappointment in the media. It sold. Between 1975 and 1980, approximately 280,000 copies were produced. Teague again produced a product that was successful despite having a small development budget. He found himself increasingly disillusioned as the 1980s rolled around. Chrysler gave up trying to convince a skeptical board that his minivan idea was a winner.

The Jeep Cherokee was one design that flew. It was produced through 1991. However, with increasing influence from France after Renault’s 1980 buy in, Teague knew his time was up. He added new badges to La Regie’s production and, voila, the Renault 9 became the AMC Alliance …). But that wasn’t Teague’s thing so he left in 1984. PPG’s last freelance job was the bizarre Alpine A310-based Wedge car concept. This was before he retired.

Teague was a car enthusiast more than many of his contemporaries. Teague owned over 300 cars, and spent his spare time surfing swap meets or using spanners. In 1991, he spoke out to Automobile Quarterly and said that he finally had a collection of classic cars from 1902 to the AMX III which reflected the great eras in automobile history. Teague, who had suffered from a long and severe illness, died in May that year. He was an easygoing, charming man who often dismissed his career as a long streak of luck and was known for playing down his accomplishments. “I should have worked harder, but my mom always said that it was better to be a has-been rather than a never was. This humility cost him dear.